The 10 Year Yield...explained.

Don't believe everything you read on the internet. Especially when it comes to financials.

The internet is a great resource for investors. At the same time it can be a swamp of financial disinformation. Between stock pumpers, TikTok options strategists, crypto everything and bimonthly Gamestop Manias it seems that each week some new financial trend takes the world by storm. This week’s trend is the 10 year yield! Fortunately this isn’t a new trend, but something that’s been around for a long time. Unfortunately I’ve read so much disinformation about it on Twitter that I felt a little write up might be beneficial for investors who truly want facts about the financial market.

Rates are not rising…yet

First things first. Rates have not risen. You may hear people on CNBC, the internet, etc. talking about rising rates, that’s because they are using rates and yields interchangeably. This is not correct. You can look at the Fed Funds Rate anytime you’d like via FED St. Louis's Website

By the way if you are a data driven investor this site should be one of your go-to resources along with the SEC, FINRA, CFTC and a few other key datacentric sites that help you get a top down view of markets and the economy, but I digress. As we can see, rates have not risen and according to Chair Powell they will not rise in the near future.

But the 10 year yield is rising:

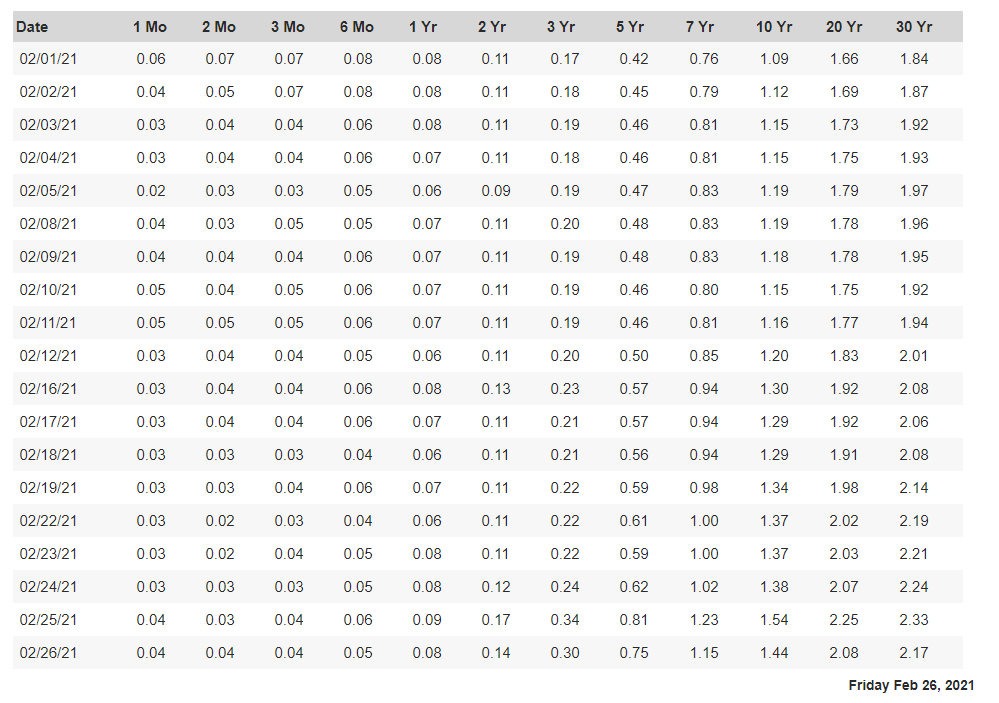

See the chart on Treasury.gov

If you look at the 10 year at the start of February it was 1.09 on 2/1. It spiked to as high as 1.54 on 2/25. So what gives? First an explanation of how these are calculated. Per the treasury.gov website:

Key phrase: “These market yields are calculated from composites of indicative, BID-SIDE market quotations (not actual transactions) obtained by the Federal reserve Bank of NY at or near 3:30 PM each trading day.”

Simple language, these yields are calculated based on the price investors are willing to buy them at. Why does this matter?

Quick Bonds Primer

A bond is a debt instrument. It’s an IOU. You are loaning money to the bond issuer. In return they will give you back a set amount of money (called the face value of the bond) and an interest payment (called the coupon rate) at a fixed time interval.

So let’s say your local city government wants to build a park. They may issue municipal bonds.

We’ll say the face value of the bond is $1000 and the coupon rate is 2.5% per year paid annually, the bond is for 5 years. That means every year for 5 year they will pay you 2.5% of $1000. If you pay the $1000 face value of the bond your yield is 2.5% or $25 per year.

But what if nobody wants to pay the face value of the bond? What if you being the shrewd investor you are, offer $980 for the bond? The face value of the bond is still $1000. And the municipality is obligated to pay 2.5% of the FACE VALUE per year. This means the payout is the same $25 per year. But you get an additional $20 if you hold this bond to maturity because while you paid $980, the FACE VALUE is still for $1000. This means the bond would yield $145 ($25*5 plus $20) on your investment of $980 over 5 years. What is the return on your investment now? Close to 2.95%

This is what’s called yield to maturity. Notice that nothing about the bond changed…except the price you were willing to pay for it. This is the biggest thing to understand about bonds. The face value and coupon rate are contractual obligations. They do not change based on the going market rate for the bond. A bond can yield more or even less than the coupon rate depending on whether the bond is trading at a premium or discount due to market conditions.

So What’s Going on with the 10 Year:

By now a savvy investor such as yourself has probably figured it out. Rates are not moving (contrary to what you keep hearing). Yield to maturity is what is moving. As we saw in the example above what causes yield to maturity to move is lender/investors not paying the face value for the bond.

So why is yields rising a problem? Think about it…what would motivate someone to not want to lend to the government? Theoretically these are about as safe an investment as you can get. You can leverage the interest and reinvest it in other assets. It’s almost as good as free money.

Unless you believe that the return you will generate is so little, that you will lose some of the value of your money due to inflation. In that case you’ll expect the government to give you more of an incentive to lend to them.

This is the problem right now — nobody wants government bonds. These trade on the open market like stocks and corporate debt. When nobody wants them, the price falls pushing the yields higher. This does a few things.

First, if you invested in them in the past assuming it was free money and leveraged the interest payment by borrowing on margin against them, the market value for your bond has now fallen. Guess what comes next? MARGIN CALL! You now have to sell some of your assets to cover the margin requirement.

Second, if yields continue to go higher, what happens next? Eventually some of the big boys who are all in on stocks may be tempted to go after a guaranteed 2-3% return. That means some money rotates out of stocks and into treasury bonds. But if treasury bonds yield 2-3%, then corporate bonds will have to pay higher yields because who would want corporate bonds at the same rate of government bonds? Government bonds are far safer. So corporate needs to offer a risk premium to incentivize the lender to assume risk.

Third if yields continue to go higher and still nobody wants the bonds, eventually the fed could be forced to raise interest rates. Because the government needs to issue bonds to fund the government spending. While they could raise taxes or cut spending, in this economy those could be harmful to the recovery from the pandemic. But when the Fed Funds Rate goes higher, so does lending rates from the banks, and that hurts young startup businesses who don’t have strong cash flows as it increases the cost of borrowing to fuel growth. It also increases yields on corporate bonds.

All of this means some investors who may have been forced to reach for stocks in this environment may be able to find bond yields that satisfy their needs for yield. This devalues stocks in general.

Hopefully this explanation of the 10 Year Yield has been simple and clear enough to answer any questions you may have when you hear “rates are rising.” Now you know that this is not entirely correct, what it really means is that bond prices are falling. Bond yields are rising and that could lead to an increase in yield from corporate, government and other bonds along with future rises in the cost of borrowing and possibly even higher interest rates. All of these aren’t generally good for the stock market. Hope this was clear and simple enough.

Until Next Time,

The Narrative.