Short Squeeze, Gamma Squeeze, Brokerage Squeeze, Retail Squeeze?

GameStop and an economic cycle in one week.

Hey fellow investors,

Last time I wrote to you, it was a warning about the dangerous path of social media influencers in the stock market. Here is a link.

Fintwit and Why Stocks Could Be Going Viral

Never could I have imagined what would have transpired since. Obviously you’ve heard about GameStop and the squeeze of a lifetime. However, there is quite a bit being written out there which is factually incomplete and inaccurate. I feel for your sake it’s worth knowing the mechanics of what is happening, why it matters and what could happen going forth:

What Happened? — The Short Squeeze

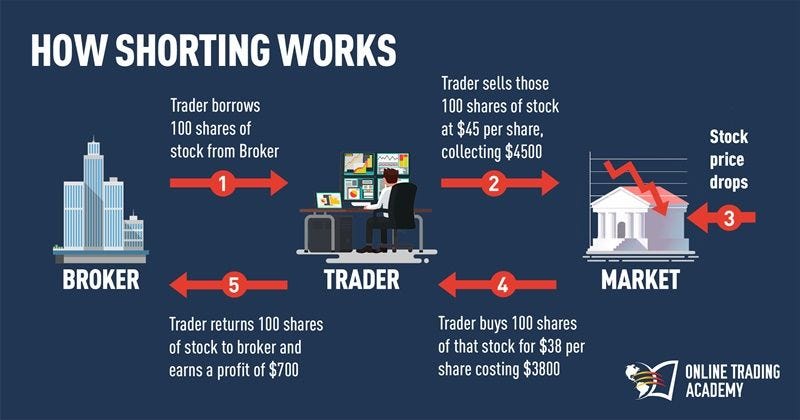

Originally the play on GameStop was initially framed as a “short squeeze.” This is true, but it’s incomplete information. Before explaining how a short squeeze works, first you have to understand the mechanics of shorting a stock.

When someone short’s a stock, they borrow the stock from someone and sell it to someone else. They do this in the hope that the price of the stock falls, and they can then buy the stock back at a lower price, return it back to the original owner and then pocket the difference. Here’s a visual from online trading academy:

So a number of large funds had decided that one way they could make money on the market or at the very least cover their investments in case of market volatility was by shorting a stock with bad fundamentals and high debt (like GameStop). They figured it wasn’t an attractive stock and they could likely go short GameStop imagining that it would continue to decrease in value. Some will then use that money to buy stocks in companies that they feel will increase in value. This is called a long/short strategy.

Sometimes they do this because they feel that by being long good stocks and short bad stocks, they can minimize the risk in the event of a market crash. If the market goes down 40%, your long position loses 40% but your short position gains 40%! This is called being market neutral. That’s why they are called hedge funds. Because they hedge against volatility by using strategies like long/short.

A large number of investors on a retail investment forum (reddit’s Wall Street Bets) decided that they would invest money as a community in GameStop. The theory being that when the price of a shorted stock goes higher, the people who’ve shorted it eventually will have to buy back the stock at a higher price. This is called a ‘short squeeze.’ Investors knew that GameStop was heavily shorted so they speculated that by buying into it, they could force the price higher as shorts eventually would have to cover their short position by buying the stock.

Why would shorts have to cover? Couldn’t they just wait it out. No. What the image doesn’t tell you is that borrowing a stock, like borrowing money means you have to pay interest on what you are borrowing. That interest varies depending on the situation. As of the time of writing the cost of borrowing $GME has now ran up to 30% for existing positions and 50% on new ones!

What Happened? — The Gamma Squeeze

What not everyone knows is that there is another group of market participants who also sells stock which they don’t own. These are called Market Makers and they sell the stock via options contracts. Options contracts are a derivative that give the purchaser the right but not the obligation to buy a set amount (normally 100 shares) of a specific asset at an agreed upon price (the strike) by an agreed upon date (expiration).

These are useful for companies who have businesses which are highly dependent on one specific commodity like oil or wheat. They can buy options contracts as hedges to ensure price stability.

Options can also be used to speculate on a stock. In this case, many of the WSB (Wall Street Bets) bought what are known as Call options speculating on the short squeeze in GameStop stock. If these options expire in the money (at or above a fixed price), then the sellers of the options (mostly Market Makers) would have to sell 100 shares of the stock at the strike price.

Here’s a visual to help you understand the math behind it from FE Options

Who are Market Makers and what do they do? Market Makers are middle men who buy and sell stock and options from interested parties. Let’s say you want to buy 12 shares in Facebook Stock. There may not be someone who wants to sell exactly 12 shares of Facebook. Maybe they want to sell 1000. Market makers step in and buy the 1000 shares and sell the 12 shares, figuring they can sell the other shares to new buyers. Sort of how GameStop buys used video games, holds inventory and sells them to people who want them. They make money by marking up what they sell and buying things at a slight markdown.

Market Makers serve as an intermediary to keep market orders flowing. Some investment banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, act as Market Makers. That being said Market Makers are gamblers in the options market. They use statistical arbitrage similar to the way casino’s do in order to make massive amounts of bets knowing that the odds are slanted in their favor.

The series of calculations they use to determine pricing is based on a complicated series of calculations. These calculations are known as ‘Greeks.’ As they sell call options, their calculations tell them what is an optimal amount of stock to keep on hand to meet the possibility of the calls expiring in the money. As the stock gets closer to expiration, if the price of the stock is rising, it’s more likely the calls end up in the money. This forces the market maker to buy shares as a hedge against the calls they sold. This is what’s called a Gamma Squeeze.

What happened — The Brokerage Squeeze

The WSB crew were able to run the stock prices of GameStop, AMC and a few other names to the roof by buying stocks and heavy volumes of call options. The more they bought, the more the shorts and the market makers had to buy to cover their stocks which they had effectively sold without owning.

Eventually some of the shorts tapped out, they covered their losses and went to lick their wounds. However others stayed short. Market makers by design cover positions mathematically, so they were covering a percent of their call positions on the way up. All of this drove the share price up but also the premiums on options up with them.

For the traders to make these trades, they have to use a brokerage. I’m assuming everyone knows what a brokerage is. However what most people don’t know is that the broker doesn’t actually buy or sell the stock. The brokerage is just a headhunter finding a party for the trade. In the case of Robinhood they have contracts to sell those trades to 4 different Market Makers. This is called order flow. When a trade is made, it’s said to be executed.

But trades don’t close instantly, due to the speed of transactions and to properly document everything, trades take time to clear and settle. This is process makes sure that everyone has the money necessary, that the exact prices are used at time of execution, that everything is documented, and afterwards the securities and money are exchanged, typically one to two days later. This requires the use of a clearinghouse. In the case of Robinhood, Robinhood has multiple legal entities. One legal entity serves as a brokerage, another serves as a clearinghouse.

Federal laws requires that clearinghouses have strict rules regarding the amounts of margin that need to be posted prior to clearing a trade. This is to prevent clearinghouses from potentially going under in some sort of financial disaster. The more volatility in the prices, the higher the risk for the clearing firms. Based on these rules and regulations, the clearing firms then have to decide whether they can take the transactions or not. Robinhood’s own clearinghouse and others like Apex Clearinghouse felt they didn’t have the liquidity necessary to continue accepting transactions. Here is WeBull CEO Anthony Denier explaining all of this in an interview with Yahoo Finance:

Brokerages were now being squeezed. What do they do? Customers want to buy, but they can’t execute the transactions. Robinhood had to restrict transactions until they could get more money to meet the clearinghouse requirements.

Why does all of this matter?

Presumably on Friday after market close, a massive amount of shares in GameStop changed hands as call options were executed. Now there are a number of unanswered questions. These merit significant attention and consideration.

First and foremost. Who has the shares?

According to Morningstar, GameStop currently has 69.75M shares outstanding. Of the 70M shares, 23M are currently in different index funds and ETFs which means they are not actively traded.

That leaves 47M shares outstanding. According to the SEC GameStop Insiders own at least 15M shares outstanding.

That means there are about 32M shares which are actively traded that are outstanding. The big question. How many of those shares are in the hands of retail investors? How many are in the hands of institutional investors? Some market pundits like to dismiss WSB as a group of know-nothing retail investors. Yet the buying power of 3M retail investors shouldn’t be dismissed. If each retail investor had bought 11 shares, they would own the entire tradeable amount of shares on the market. Considering this was a $20 stock a few weeks ago, that would be a mere $200 investment per person.

Second and also important…who needs the shares?

If you believe S3 partners, shorts still need shares to the tune of 57.83M shares still outstanding short. But you need to factor in one more component to the equation. Calls and Puts sold.

We discussed Call Options earlier, but we didn’t discuss Put Options. The Market Makers are smart. They know that for everyone who wants to buy a stock, someone else has to sell one, so just like they sell call options, they also sell put options. Last week the furious selling in call options meant Market Makers had to own stock. However they were also furiously selling put options for next week.

Put options are a way for people to hedge on a stock’s price going down. It gives the owner of the option the right but not the obligation to sell 100 shares of the stock at or a below a fixed price. So let’s say you were convinced that GME is headed to 50. You could buy the $100 put option, and if the stock goes below 100, you can buy the stock at any price below $100, and then turn around and sell it for $100. So if the stock goes to 50, you’d make $50 per share x 100 shares. Not bad.

However when you buy any option you have to pay a premium. The premium in both call and put options depends on the volatility of the stock. The more that stock is moving, the more you will pay for your option because the higher the risk to the option seller.

Here’s the kicker — IF YOU BUY A PUT AND DON’T OWN THE STOCK, YOU CAN’T EXERCISE THE PUT. We often talk about naked puts, if you sell a put, you have to have the cash available to buy the stock otherwise it’s consider naked. However if you buy a put, you have to have the stock available to exercise the option to sell the stock. Normally that’s not a big deal because in a liquid market you can always buy the stock at fair market value. This is where things get very interesting and the individual investor needs to pay attention.

Third question…What do the laws of supply and demand tell us?

We have already mathematically determined that the supply of the GME stock is rather finite at the moment (32M unless the company does a secondary share offering). We’ve also determined that the demand for the shares amounts to a demand of at least 50M shares plus a number to be determined by the options market. At this moment there are still nearly 10k calls which are in the money, meaning the sellers of the calls are on the hook to deliver 1M shares. Put buyers have also been spending 100s of dollars per share to purchase the right to sell at between 300-320 per share. The Open Interest is nearly 2k shares. That means put buyers will need to grab 200k shares to exercise those contracts.

The short demand has an external force that weighs on it — leverage. Because these are borrowed shares, the interest rates are acting as a leverage that exacerbates the problem. The shorts are highly incentivized to close at all costs, because if the price continues to rise, they run the risk of insolvency.

Added to the problem is that other funds may have money being held by the shorts. If you knew your fund was running the risk of insolvency what would you do? The old fashioned bank run to withdraw. This adds even more pressure on them to close their short positions.

However if the shorts went bankrupt, then the longs would have a problem, they’d have the same finite supply, but nobody left to sell it to.

What happens next?

This is the fascinating question. It all boils down to how committed the group is, how much risk they are willing to take, and how much cash shorts are willing to burn:

If the group is committed and holds their shares (assuming that they have the majority of the market) AND assuming that GME doesn’t issue a secondary. The laws of supply and demand say that the price will go higher. In fact they could sell puts against their shares, betting that the put buyers are buying naked, collect the premiums (currently at $100 per share) and then buy call options (assuming that the MM were selling naked) as the expiration point gets closer, put buyers and call sellers would need to buy shares to exercise their options — this would force an even higher squeeze.

If they were to do this, eventually the squeeze would either bankrupt the shorts and possibly cause liquidity issue for MM’s and/or force GME to do a secondary to avoid getting caught up in the bubble with nothing to show for it. Depending on the amount of the secondary, it would either release pressure or would result in the bubble bursting and the shorts getting let off the hook with their wounds being the interest paid and whatever prices they paid GME for the secondary shorts. If managed properly this could almost turn out to be what Ray Dalio calls a beautiful deleveraging playing out in the economy that is GameStop stock.

Otherwise if they can’t find shares, the shorts will inevitably go bankrupt. The MM are also running a risk if they continue to sell naked calls and buy naked puts.

This is where the real issue could begin:

If multiple institutions start going down…a real systemic risk exists and the market could see a crash.

This is why market makers need to stop buying and selling the options trades. In fact legislators NEED TO step in before this happens and restrict the buying and selling of ALL options on the stock to protect the market. This would also allow for the free exchange of shares by brokerages without restrictions.

However once the shorts are flushed out, and the options stop being traded, then the stock bubble bursts…because their is no demand and excess supply (and vultures will appear to short once the panic ensues).

The other path is the one that most see as the likeliest of outcomes. If some in the group decide that they want to take profits and begin selling shares, this lets off some of the pressure on shorts. Also if the price in the stock moves enough to the downside, some in the group who’ve bought on margin could face margin calls. This would release their shares to the market where the market makers would likely gobble them up. All of this would again likely force GME into a secondary. This could result in a chain reaction which brings the supply/demand function closer to equilibrium with each step.

I’m not going to say whether someone should be or shouldn’t be in this trade, and how to play it. I’m just stating the facts as I see them from the laws of supply and demand. I also just wanted to share with you because I genuinely see a potential systemic risk at hand. Not saying that a crash is imminent. However watch this situation closely. Just because GME is a small portion of the market doesn’t mean it’s meaningless. The question is leverage. How much of the market currently is being held on borrowed money? It was leverage that took down the financial system in 08, and leverage can do it again.

Stay vigilant, stay safe. From COVID and the Markets.

—The Narrative.