A storm brewing?

Thinking about impacts of natural disasters on financial markets.

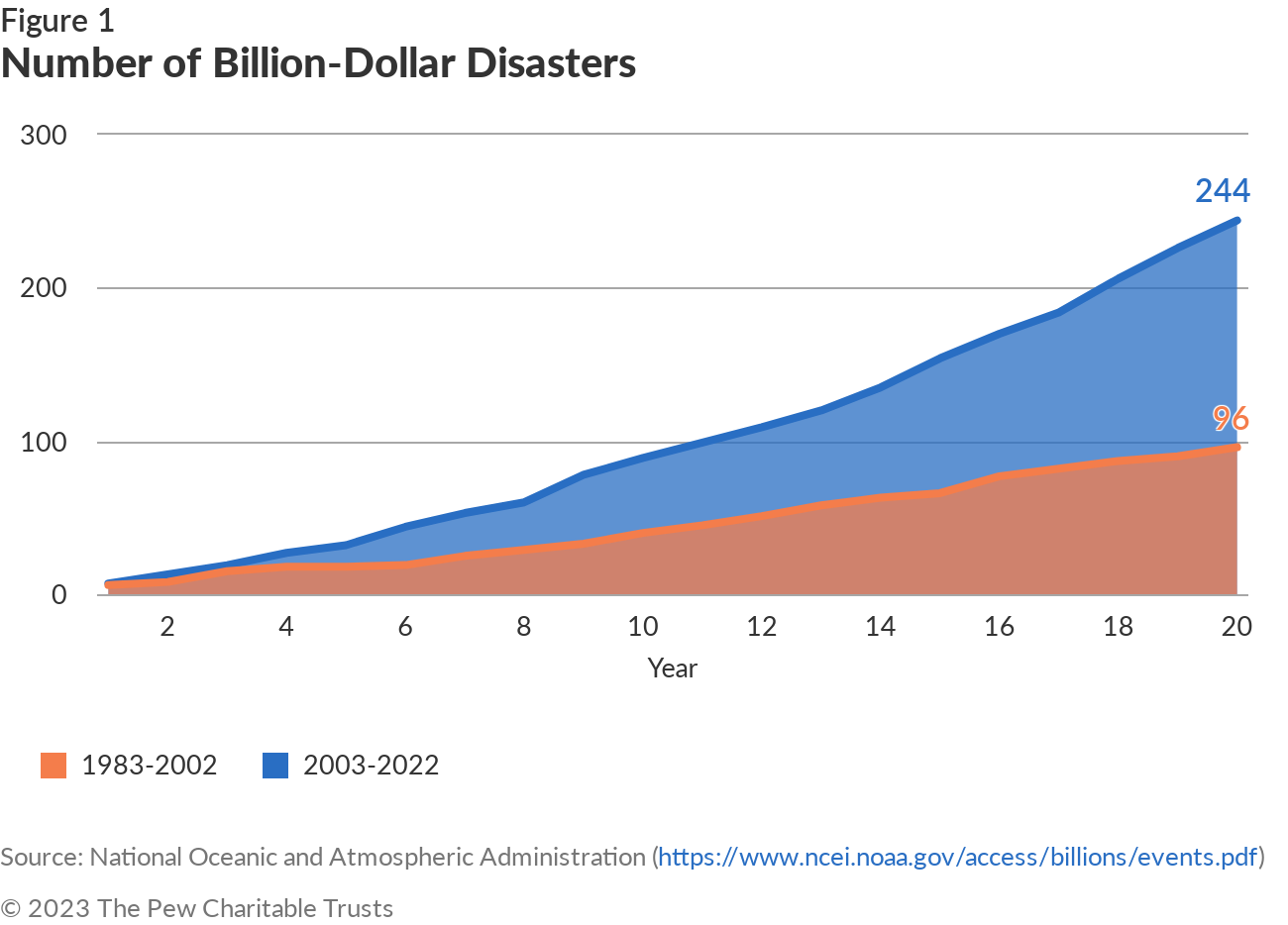

As the LA wildfire’s rage. Damage estimates are already in the hundreds of billions of dollars. This comes on the heels of a year where natural disasters caused an estimated 300 billion dollars of damage. If it seems that large scale disasters are happening with greater frequency, it’s because they are. Over the past 20 years, the number of billion dollar disasters has increased 150%.

During that same time frame, the monetary damages have increased by nearly 300%.

With this in mind I want to explore whether natural disasters could begin to have a destabilizing effect on financial markets?

I think there are 3 issues that markets need to be thinking about:

Does insurance truly have unlimited pricing power?

Can an over concentrated real estate market exacerbate risk?

Tail risks of catastrophe (CAT) bonds

Limits to Insurance Pricing Power

One assumption I’ve seen in financial markets is that insurance will always earn more after these disasters, via a combination of de-risking and premium increases.

This belief has a logical fallacy inherent in it. It overlooks the fact that most of the premiums come from a handful of properties. And the locations of these properties matter. Consider what properties insurers view as being most “at-risk” — Florida coastal properties and properties in fire risk areas such as the Pacific West Coast rank highest in this category. These properties have two things in common (besides their high risk nature for insurers):

They tend to be higher value properties (see map)

As such they are owned by the individuals who are NOT as price sensitive to insurance premiums.

In dropping these properties, insurers have sacrificed the significant premiums that they pay out. At the same time they’ve raised prices and lowered coverages on less riskier properties. But these properties may not have the incentives nor financial means to absorb these increases.

The cost of coverage on homeowners

Homeowners insurance has gone up at a compounded rate of 5% per year over the past 20 years.

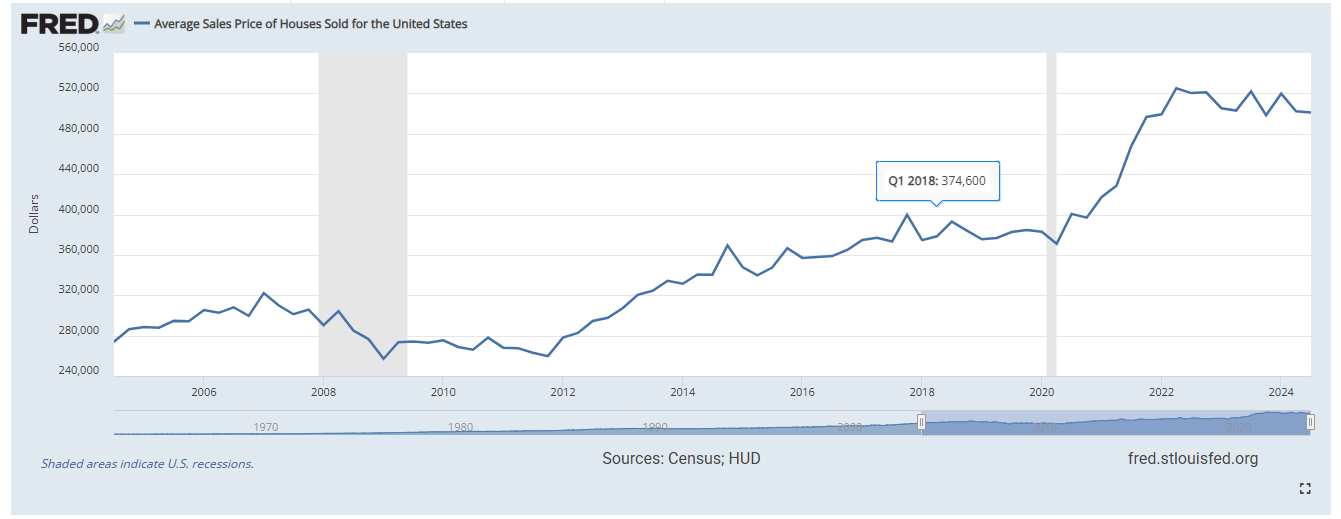

At the same time the average sale price for a US home has increased at a compounded rate of 3% per year over the past 20 years.

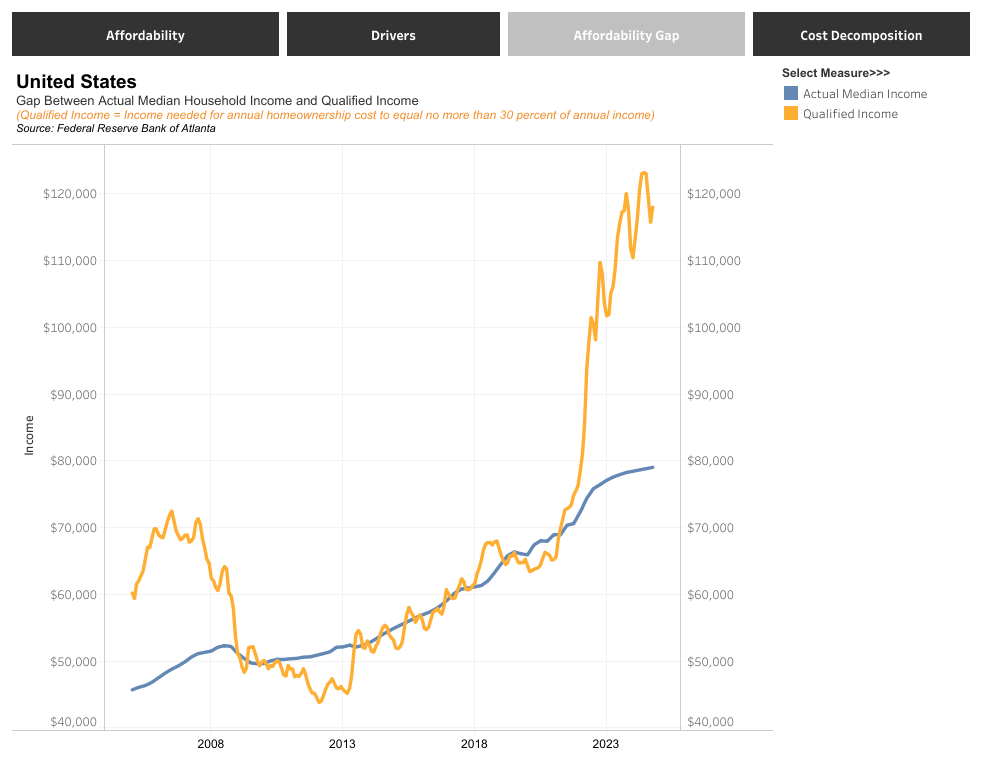

Said differently, in the past 20 years the cost to insure a home has gone up 50% relative to the home’s value. This begs the question, at what point does the insurance become so unaffordable that it causes financial distress for homeowners? For some owners, dropping coverage is not an option due to their mortgage requirements. Could insurance get to a point where it makes holding a mortgage financially unsustainable? I’ve heard whispers from multiple clients that escrow is becoming a real challenge for them. The stats back this up. We are dealing with an affordability crisis in the United States.

Home ownership costs have spiked beyond median income, to the point that for many Americans 45% of their income is being set aside per year to pay for the costs of homeownership. The question is how much further can this spread stretch?

Pricing Power of Insurance in Rentals

American homeownership is at lower levels than it was 20 years ago. At the same time the housing supply has increased by a meager 20% in the past 20 years, less than 1% per year compounded. Home vacancies though are down nearly 3%. Said differently, less people own more homes, but the homes aren’t empty…they are being rented out either as long term or short term rentals.

Long term rentals do have certain advantages over short term rentals. Their demand is more inelastic and they tend to have more pricing power. This doesn’t mean however that said pricing power is unlimited. Nearly 30% of American housing is occupied by 1 person. However more than 70% of housing units are designed with 2 or more bedrooms.

This would suggest that while pricing power in long term rentals is likely strongest in terms of it’s ability to pass insurance costs down to renters, it’s not unlimited. At a certain point single member households would likely look to consolidate. Just because it’s hard to build, doesn’t mean that properties can’t be used more efficiently.

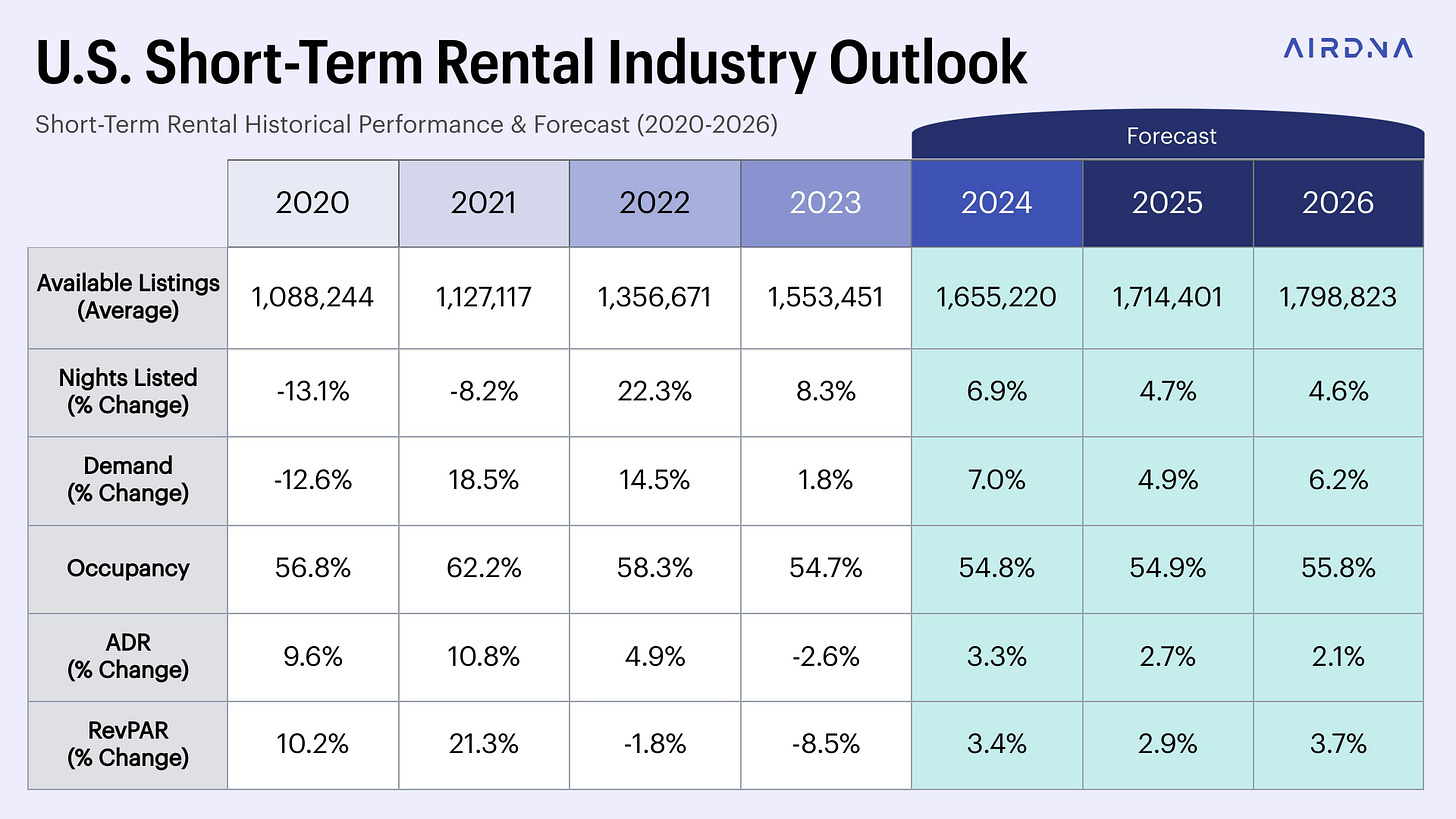

Short term rentals are a different story. In 2023, there were 2.5M rental listings hosted by 785k hosts in the US on AirBNB. Unlike a primary residence or a long term rental, short term rentals don’t fulfill a basic human need. Because of this they have very little pricing power.

As seen in this graphic from AirDNA, revenue per available room dropped meaningfully in 2023, it’s 2nd straight year of decline. Not good since as we’ve previously seen that real estate is getting more expensive to own and maintain. Mix that with the leverage which is inherent in investment properties (typically at 4-6x) and the fact that owners typically hold multiple properties. You now have a potent cocktail for distress.

Is a storm brewing?

It’s easy to see that stress is building in housing. When that stress causes economic injury is unclear. Perhaps this may be why insurance companies are so eager to issue catastrophe bonds. Because they know that relying on premiums to go up forever isn’t sustainable. As a result the amount of capital outstanding in these CAT bonds has increased nearly 10 fold in the past 20 years.

CAT bonds have also performed very well for investors. In exchange for tail risk, investors have gotten equity like returns with low volatility and low correlation to other asset classes. Insurers have been able to pay out CAT bonds with a mix of good market returns and the bounty of increasing premiums. Still, one has to think that eventually so much shifting towards tail risk is going to cause a problem. Especially when bankers create a way to apply leverage to these bonds. (Synthetic Tranches of Collateralized CAT Bonds anyone?)

Conclusion

The purpose for writing this piece isn’t because I have a solution, but rather that I have questions which trouble me:

Is there any risk to housing created by rising costs of insurance?

I believe there is. I think we could see costs of insurance lead to abandonment of properties within the next few years.

Is that risk exacerbated by the concentration of ownership in housing and poor usage of existing housing?

I believe so. I think we may see distressed short term rentals being converted to long term, or sold on the market at discounts to current prices.

Is there a risk that markets get overly cozy with Catastrophe Bonds?

Absolutely. It’s a tale as old as time. New product comes out and offers high returns with less correlated risks. Market splurges because the quantitative metrics are fantastic. Wall Street finds some way to leverage the product. Something breaks and causes an economic panic.

Is there some cataclysmic event in which Risks 1,2 and/or 3 create a significant negative event for financial markets.

I think this is absolutely the case. In the midst of a housing recession, a significant natural disaster in a densely populated area topples some over leveraged fund which went ham on a specific CAT bond with previously never before seen losses.

Is there some way to profit from this?

I have no earthly idea, but if someone smarter than me reads this and figures it out, let me know.